Value-form

General definition

The value-form or form of value is a concept in Karl Marx’s critique of the political economy.[1] It refers to a socially attributed characteristic of a commodity (any product traded in markets) which contrasts with its tangible use-value or utility (its "useful form" or "natural form").

The concept is introduced in the first chapter of Das Kapital[2] where Marx argues economic value becomes manifest in an objectified way only through the form of value established by the exchange of products. In other words, what something is economically "worth" can be expressed only relatively, by relating, weighing, comparing and equating it to amounts of other tradeable objects (or to the labour effort or sum of money which those objects represent).[3]

The "problem" of a form-analysis of value

The question that Marx's value-form analysis intends to answer, is essentially how the value of products is expressed in ways which acquire an objective existence in their own right (ultimately as money), and how these product-values can change, quite independently of the valuers who trade in them.[4] Marx argued that neither the classical political economists nor the vulgar economists who succeeded them were able to explain satisfactorily how that worked, resulting in serious theoretical errors. Marx's idea can be traced back to his 1857 Grundrisse manuscript where he contrasted communal production with production for exchange.[5] Marx notes in Das Kapital that:

"It is one of the chief failings of classical political economy that it has never succeeded, by means of its analysis of commodities, and in particular of their value, in discovering the form of value which in fact turns value into exchange-value."[6]

Similarly, in vulgar (or vulgar Marxist) economics, the commodity is simply a combination of use-value and exchange-value. That is manifestly not Marx's own argument at all.[7] As he explains in Capital, Volume III, business competition among producers centres precisely on the discrepancies between the socially established value of commodities and their particular exchange-value.[8] Marx believed that correctly distinguishing between the form and content of value was essential for the logical coherence of the labour theory of value,[9] and he criticized Adam Smith specifically because Smith:

"...confuses the measure of value as the immanent measure which at the same time forms the substance of value [i.e. labour-time], with the measure of value in the sense that money is called a measure of value. With regard to the latter, the attempt is then made to square the circle — to find a commodity whose value does not change, to serve as a constant measure for others. On the question of the relation of the measure of value as money to the determination of value by labour-time, see the first part of my work. This confusion is also to be found in [David] Ricardo in certain passages."[10]

Althusserian interpretation

The value-form is often regarded as a difficult, obscure or even esoteric idea by scholars, and there has been considerable debate about its real theoretical significance. Mark Blaug stated: "The reader will miss little by skipping over the pedantic third section of chapter 1 on which the hands of Hegel lie all too heavily."[11] In his "Preface to Capital Vol. 1," the French philosopher Louis Althusser asserted:

"The greatest difficulties, theoretical or otherwise, which are obstacles to an easy reading of Capital Volume One are unfortunately (or fortunately) concentrated at the very beginning of Volume One, to be precise, in its first Part, which deals with ‘Commodities and Money’. I therefore give the following advice: put the whole of Part One aside for the time being and begin your reading with Part Two..."[12]

Althusser's suggestions were taken up by many Marxists.[13] However, Marx not only very deliberately and explicitly made an effort to state his interpretation of commodity trade with absolute clarity in his first chapters; it is also essential to understand all the rest, and that is exactly why Marx stated it at the beginning.[14]

Academic difficulties

Probably the difficulty Marxist academics have had with Marx's own text is because, abstractly, economic value refers at the same time to quantitative and qualitative dimensions, which can be stated according to both absolute and relative criteria, and expressed as:

- a relationship,

- a subjective orientation

- an attribute

- an object in its own right.

From the use of the expression "value" it may therefore not be immediately obvious what kind of valuation or expression is being referred to, it depends on the theoretical context.[15] Marx himself rarely if ever defended his finished theory of value in scientific debate, and left it to his followers to clarify issues and problems in his unfinished manuscripts. Because he uses the term "value" somewhat differently in different contexts, academic disputes arise about what exactly he meant.[16]

In addition, official economics typically takes it for granted that the exchange processes on which markets are based already exist and will occur, and that prices already exist, or can be imputed. This assumption is overturned only there where markets still have to be brought into being. In modern economics, the "value" of something is defined either as a money-price, or as a personal (subjective) valuation.

According to orthodox economics, money originates as a medium of exchange to minimize the transaction costs of barter among utility-maximizing individuals. Such an approach is very different to Marx's historical interpretation of the formation of value. In Marx's theory, the "value" of a product is something separate and distinct from the "price" it happens to fetch (goods can sell for more than they are worth, or less, i.e. they are not necessarily worth what they happen to sell for).[17]

Value-form and commodity fetishism

The theory of the forms of value is the basis for Marx's concept of commodity fetishism, which concerns how the independent power acquired by the value of tradeable objects is reflected back into human thought, and more specifically into the theories of the political economists about the market economy.

It is a very basic insight of all economics, that human valuations have their origin in people's ability to prioritize and weigh up behavioural responses according to self-chosen options. That is indeed the conceptual basis of the "self-interested, utility-maximizing economic actors" used in economic models.

But things become more complicated, because the "things" endowed with value gain a "life of their own". They begin to act in their own right, compelling people to adjust their behaviour to market trends which they are no longer in control of. Not only does it begin to seem like "the tail wags the dog", but the tail may indeed wag the dog. The way that economic cause and effect observably appear to the individual, may - according to Marx - be the exact inverse of the real economic process, considered in its totality. This has a profound influence on economic theorizing, in its attempt to unravel the true relationship between economic causes and effects.

Basic explanation

Marx initially defines a product of human labour which has become a commodity (in German: Kaufware, i.e. merchandise, ware for sale) as being simultaneously:

- (1) a useful object that can satisfy a want or need (a use value); this is the value of object considered from the point of view of consuming or using it, referring to its observable material form, i.e. the tangible, observable characteristics it has which make it useful, and therefore valued by people, even if the use is only symbolic.

- (2) an object of economic value generally; this is the value of the object considered from the point of view of its earnings potential, its sale value or its cost of production ("commercial value"). The reference here is to the social form of the product which is not directly observable.

The “form of value” (a reference to phenomenology in the classical philosophical sense used by Hegel) then refers to the specific ways of relating through which “what a commodity is worth” happens to be socially expressed in trading processes, when different products and assets are compared with each other. Practically speaking, Marx argues that the product values cannot be directly observed and can become observably manifest only as exchange-values, i.e. as relative expressions, by comparing their worth to other goods they can be traded for. This causes people to think value and exchange-value are the same thing, but Marx argues they are not; the content, magnitude and form of value must be distinguished, and according to the law of value, the exchange value of products being traded is determined and regulated by their value.

Historical change

Marx argues that the form of value is not "static" or "fixed once and for all", but rather, that it develops logically and historically in trading processes from very simple, primitive expressions to very complicated or sophisticated expressions. Subsequently he also examines the various "forms" taken by capital, the "forms" of wages, and so forth. In each case, the "form" denotes how a specific social or economic relationship among people is expressed or symbolized.

Initially, in primitive exchange, the form that economic value takes does not even involve any prices, since what something is "worth" is very simply expressed in (a quantity of) some other good (an occasional barter relationship). In the earliest forms of exchange of goods, Marx says,

"Custom fixes their values at definite magnitudes... At this stage, therefore, the articles exchanged do not acquire a value-form independent of their own use-value, or of the individual needs of the exchangers".[18]

But at the most abstract, developed level, the value form is only a purely monetary relationship between objects, or an abstract earnings potential or credit provision based on some assumptions, which may not even refer to any tangible object of trade anymore at all. At that point, it appears that the value of an asset is simply the amount of income which could be obtained if the asset was traded under certain conditions.

Social relations

By analyzing the value-form, Marx aims to show that when people bring their products into relation with each other in market trade, they are also socially related in specific ways (whether they like it or not, and whether they are aware of it or not), and that this fact very strongly influences the very way in which they think about how they are related.[19] It influences how they will view the whole human interactive process of giving and receiving, taking and procuring, sharing and relinquishing, accepting and rejecting - and how to balance all that. For example, Marx writes a bit theatrically:

"We will discover in the progress of our inquiry, that the economic character masks ["Charaktermasken" in the German original] of persons are only the personifications of economic relationships, where persons face each other as their bearers. Namely, what distinguishes the commodity owner from the commodity is the circumstance that every other commodity counts for each commodity only as the appearance-form of its own value. A born leveller and a cynic, the commodity is constantly ready to exchange not only soul, but body, with each and every other commodity... The owner makes up for this lack in the commodity of a sense of the concrete, physical body of the other commodity, by his own five and more senses (...) commodities must be realized as values before they can be realized as use-values. On the other hand, they must stand the test as use-values before they can be realized as values.(...) In their difficulties, our commodity-owners think like Faust: 'In the beginning was the deed'. Thus they act already before they have thought it out."[20]

Thus, the value-form of products does not merely refer to a “trading valuation of objects”; it refers also to a certain way of relating or interacting, and a mentality, among human subjects who internalize the value-form, so that the manifestations of economic value become regarded as completely normal, natural and self-evident in human interactions (a "market culture" which is also reflected in language use). Marx's slightly surreal description of what goes on in commodity exchanges highlights not only that value relationships appear to exist between commodities quite independently of the valuers, but also that people accept that these relationships exist even although they do not understand exactly what they are, or why they exist at all. They often participate in markets without knowing much at all about how they work.

Objectification

Marx’s argument is that in order to be able to trade, people must objectify (objectively express) the value of goods produced, but it turns out that, in doing so, they are actually also objectifying and comparing the value of their own labour-efforts. Most abstractly, the quantities of money for which products are traded express claims to quantities of society's labour in general, or “abstract labour”. So by equating and comparing the value of their products in exchange, people at the same time equate and compare the value of their labour efforts, even if they are completely unaware of that; and what a product is worth becomes dependent on, and changes according to, what other products are worth, even regardless of subjective evaluations of what the product is worth.

This objectification process has two main effects:

- (1) value relations gain an independent, objective existence which begins to regulate and dominate human life, and to which all people must adjust their behaviour, whether they like it or not. They internalize the value-form by adjusting to its effects (this is called “the forces and laws of the market”). Simply put, if human valuations originate in people's ability to prioritize and weigh up behavioural responses according to self-chosen options, the very meaning of their choices, and the language in which they are expressed, will be strongly influenced by the surrounding world ordered by the value-system.

- (2) a consequent tendency towards a reifying inversion in human awareness (subjects become treated as things, and things become treated as active subjects, while means become ends, and ends become means). Even although the values attributed to products exist only as a social effect of how people are relating and related, it begins to look like value is actually an intrinsic property of products; the way average values change, begins to lead a "life of its own" which individuals and groups are unable to control and must adjust to, like it or not. Traders become primarily concerned with the objective trading value of products, rather than any other kind of valuation, regarding products as "overvalued" or "undervalued" according to the "state of the market".

The combination of (1) and (2) mean that regardless of how one happens to think or choose, one must necessarily conform to the structure of value relations which exists in capitalist society, quite independently of one’s will or awareness. It is not that value relations are “only objective” or “only subjective” (value relations obviously could not exist at all, without humans making and accepting valuations, whether explicitly or implicitly) but rather that the objectification of value becomes a tangible, practical reality that one simply cannot get away from. A relationship is established between things which, although it originates in human valuations, escapes from the control of individuals, groups and nations.

Textual sources

Marx’s explanation of the value-form originated in his Grundrisse manuscripts, and in ideas expressed his 1859 book A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, which failed to sell many copies. It is already clearly evident in his manuscript of Theories of Surplus Value (1861–63). Marx first explicitly described the concept in an appendix to the first (1867) edition of Das Kapital,[21] but this appendix was dropped in a second edition, where the first chapter was rewritten to include a special section on the value-form at the end.

In a preface to the first edition of Das Kapital, Marx stated

"I have popularised the passages concerning the substance of value and the magnitude of value as much as possible. The value-form, whose fully developed shape is the money-form, is very simple and slight in content. Nevertheless, the human mind has sought in vain for more than 2,000 years to get to the bottom of it…”[22]

Marx gives various reasons for this, but the main obstacle seems to be that trading relations refer to societal relations which are not necessarily observably manifest, and therefore can only be inferred or analyzed with the aid of highly abstract ideas. The quote clarifies that Marx thought that the value-form of commodities is not simply a feature of capitalism, but is associated with the whole history of commodity trade.[23]

According to Marx, the Greek philosopher Aristotle had already described the basics of the value-form when he argued[24]) that an expression such as "5 beds = 1 house" does not differ from "5 beds = such and such an amount of money", but according to Marx, Aristotle's analysis "suffered shipwreck" because he lacked a clear concept of value. By this Marx meant that Aristotle was unable to clarify the substance of value, i.e. what exactly was being equated in value-comparisons, or what was the common denominator commensurating different goods. Aristotle thought the common factor must simply be the demand for goods, since without demand for goods that could satisfy some need or want, they would not be exchanged. According to Marx, the substance of product-value is human labour-time in general, labour-in-the-abstract or "abstract labour". This value exists quite independently of the particular forms that exchange may take, though obviously value is always expressed in some form or other.

Marx argues that only when market production is highly developed, that it becomes possible to understand what economic value actually means in a comprehensive and theoretically consistent way, separate from other sorts of value (like aesthetic value or moral value). He states:

"The secret of the expression of value, namely the equality and equivalence of all kinds of labour because and insofar as they are human labour in general, could not be deciphered until the concept of human equality had already acquired the permanence of a fixed popular opinion. This however becomes possible only in a society where the commodity-form is the universal form of the product of labour, hence the dominant relation is the relation between men as possessors of commodities”.[25]

He discusses the notion of the formal equality of market actors more in the Grundrisse.[26] Marx admitted that the value-form was a somewhat difficult notion but he assumed “a reader who is willing to learn something new and therefore to think for himself.”[27] In a preface to the second edition of Das Kapital, Marx said that he had “completely revised” his treatment, because his friend Dr. Louis Kugelmann had convinced him that a “more didactic exposition of the form of value” was needed.[28]

The development of the value-form in the history of trading relations

Marx distinguishes between four successive steps in the process of trading products, i.e. in the circulation of commodities, through which fairly stable and objective value proportionalities (Wertverthaltnisse in German) are formed which express "what products are worth". These steps are:

- 1. The simple value-form, an expression which contains the duality of relative value and equivalent value.

- 2. The expanded or total value-form, a quantitative "chaining together" of the simple forms of expressing value.

- 3. The general value-form, i.e. the expression of the worth of all products reckoned in a general equivalent.

- 4. The money-form of value, which is a general equivalent used in trading (a medium of exchange) which is universally exchangeable.

These forms are different ways of symbolizing and representing what goods are worth, to facilitate trade and cost/benefit calculations. The simple value-form does not (or not necessarily) involve a money-referent at all, and the expanded and general forms are intermediary expressions between a non-monetary and a monetary expression of economic value. The four steps are an abstract summary of what essentially happens to the trading relationship when the trade in products grows and develops. The four steps are not necessarily an adequate literal description of what historically happens (see below).

Simple value-form

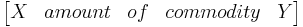

The simplest value-form expression can be stated as the following equation:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

X quantity of commodity A is worth Y quantity of commodity B

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

where the value of X(A) is expressed relatively, as being equal to a certain quantity of B, meaning that A is the relative form of value and B the equivalent form of value, so that B is effectively the value-form of (expresses the value of) A. If we ask "how much is X quantity of commodity A worth?" the answer is "Y quantity of commodity B". This simple equation, expressing a simple value proportion between products, however permits of several variations, mutations, or possibilities of differences in valuation emerging within the circulation of products:

- the absolute value of A changes, but the absolute value of B stays constant; in this case, the change in the relative value of A depends only on a change in the absolute value of A (The absolute value, Marx argues, is the total labour cost on average implicated in making a commodity).

- the absolute value of A stays constant, but the absolute value of B changes; in this case, the relative value of A fluctuates in inverse relation to changes in the absolute value of B, meaning that if B goes down then A goes up, while if B goes up then A goes down.

- the values of A and B both change in the same direction and in the same proportion. In this case, the equation still holds, but the change in absolute value is noticeable only if A and B are compared with a commodity C, where C’s value stays constant. If all commodities increase or decrease in value by the same amount, then their relative values all remain exactly the same.

- the values of A and B change in the same direction, but not by the same amount, or vary in opposite directions.

These possible changes in valuation enable us to understand already that what any particular product will trade for is delimited by what other products will trade for, quite independently of how much the buyer would like to pay, or how much the seller would like to get in return. Value should not be confused with price here, however, because products can be traded at prices above or below what they are worth (implying value-price deviations; this complicates the picture and is elaborated only in the third volume of Das Kapital). For simplicity's sake, Marx assumes initially that the money-price of a commodity will be equal to its value; but in Capital Vol 3 it becomes clear that the sale of goods above or below their value has a crucial effect on profits.

The main implications of the simple relative form of value are that:

- the value of an individual commodity can change relative to other commodities, although the real cost in labour of that particular commodity stays constant, and vice versa, the real labour cost of that particular commodity can vary, although its relative value remains the same; this means that goods can be devalued or revalued depending on what happens elsewhere in the trading system and on changes in the conditions of producing them elsewhere. It would therefore be wrong to claim, as some Marxists[29] argue, that for Marx "economic value is labour"; rather, economic value really refers to the current social valuation of labour effort implicated in products. Indeed Marx himself is quite clear that living labour itself has no value, although it has a price and creates product-value; only labour power and products of human labour have an economic value (resources not produced by human labour can only have a price, determined ultimately by their scarcity relative to the demand for them, and by their income-earning potential).

- that the absolute and relative values of commodities can change constantly, in proportions which do not exactly compensate each other, or cancel each other out, via haphazard adjustments to new production and demand conditions. Thus, contrary to the concept of general equilibrium, Marx did not believe at all, even at the most fundamental level, that the circulation process itself offers any guarantees that the gains and losses incurred by trading parties will somehow "balance out"[30] (the secret of the economic balance is to be found instead in the maintenance of the social relations of production, specifically the enforcement of property rights).[31] If there is a relative balance in the exchange process as such, that is because people refuse to trade on terms which they regard as excessively unfavourable, or do so only with the greatest reluctance (see also Unequal exchange).

But, Marx also argues that, at the same time, such an economic equation accomplishes two other things:

- the value of specific labour activities is implicitly related in proportion to the value of labour in general, and

- private labour activities, carried out independently of each other, are socially recognized as being a fraction of society’s total labour.

Effectively, a social nexus (a societal connection or bond) is established and affirmed via the value-comparisons in the marketplace, which makes relative labour costs (the expenditures of human work energy) the real substance of value. Obviously, some assets are not produced by human labour at all, but how they are valued commercially will nevertheless refer, explicitly or implicitly, directly or indirectly, to the comparative cost structure of related assets which are labour-products. A tree in the middle of the Amazon Rain Forest has no commercial value where it stands. We can estimate its value only by estimating what it would cost to cut it down, what it would sell for in markets, or what income we could currently get from it - or how much we could charge people to look at it. Imputing an "acceptable price" to the tree assumes that there already exists a market in timber or in forests which tells us what the tree would normally be worth.

Expanded value-form

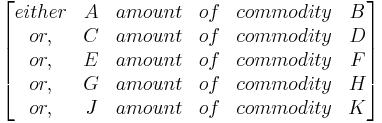

In the expanded value-form, the equation process between quantities of different commodities is simply continued serially, so that their values relative to each other are established, and they can all be expressed in some or other commodity-equivalent. However, Marx argues that, as such, the expanded value-form is practically inadequate, because to express what any commodity is worth might now require the calculation of a whole “chain” of comparisons, i.e.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

X amount of commodity A is worth Y commodity B, is worth Z commodity C … etc.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

What this means is, that if A is normally traded for B, and B is normally traded for C, then to find out how much A is worth in terms of C, we first have to convert the amounts into B (and maybe many more intermediate steps). This is obviously inefficient if many goods are traded at the same time.

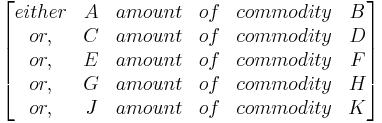

General value-form

The practical solution in trade is therefore the emergence of a general value-form, in which the values of all kinds of bundles of commodities can be expressed in amounts of one standard commodity (or just a few standards) which function as a general equivalent. The general equivalent has itself no relative form of value in common with other commodities; instead its value is expressed only in a myriad of other commodities.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

=

=

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

In ancient civilizations where considerable market trade occurred, there were usually a few types of goods which could function as a general standard of value. This standard was used for value comparisons; it did not necessarily mean that goods were actually traded for the standard commodity.[32] In this sense, the "general value-form" fails to solve the practical problem that if trader A wants to trade X for Y, and trader B wants to trade Y for Z, no trade can occur at all unless e.g. a trader C can act as intermediary, and can trade Y for X, and Z for Y. In other words, people have to ensure that they have the right things to offer in exchange for what they want, because otherwise there is no deal; and they might have to receive back something in exchange that they don't want, but which they can later trade for something they do want. This rather cumbersome problem is solved with the introduction of money - the owner of a product can sell it for money, and buy another product he wants with money, without worrying anymore about whether the thing offered in exchange for his own product is indeed the product that he wants himself. Now, the only limit to trade is the development of the market, i.e. the extent to which products, services and assets are offered for sale as marketable things, rather than being things which according to law, custom and religion may not be traded.

Money-form of value

Just because quantities of goods can be expressed in amounts of a general equivalent, which acts as a reference, this does not mean that they can necessarily all be traded for that equivalent. The general equivalent may only be a sort of yardstick used to compare what goods are worth. Hence, the general equivalent form in practice gives way to the money-commodity which is a universal equivalent, meaning that (provided people are willing to trade) it possesses the characteristic of direct and universal exchangeability in precisely measured quantities.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

=

=

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

But for most of the history of human civilization, money was not actually universally used, partly because the prevailing systems of property rights and cultural custom did not allow many goods to be sold for money, and partly because many products were distributed and traded without using money. Also, several different "currencies" were often used side by side. Marx himself believed that nomadic peoples were the very first to develop the money-form of value (in the sense of a universal equivalent in trade) because all their possessions were mobile, and because they were regularly in contact with different communities, which encouraged the exchange of products.[33] When money is generally used in trade, money becomes the general expression of the value-form of goods being traded; usually this is associated with the emergence of a state authority issuing legal currency. At that point the value-form appears to have acquired a fully independent, separate existence from any particular traded object (behind this autonomy, however, is the power of state authorities or private agencies to enforce financial claims).

Commenting on the riddle of the money-fetish, Marx notes that:

"What appears to happen is not that a particular commodity becomes money because all other commodities universally express their values in it, but, on the contrary, that all other commodities universally express their values in a particular commodity because it is money. The movement through which this process has been mediated vanishes in its own result, leaving no trace behind. Without any initiative on their part, the commodities find their own value-configuration ready to hand, in the form of a physical commodity existing outside but also alongside them. This physical object, gold or silver in its crude state, becomes, immediately on its emergence from the bowels of the earth, the direct incarnation of all human labour. Hence the magic of money."[34]

According to Marx's theory of money,[35] the money-form of value (whether bullion, coinage, paper or money of account) fulfills a number of social functions at the same time:

-

-

-

-

-

- It is a universal equivalent, which can in principle exchange for any product offered for sale.

- It is a means of exchange, facilitating the circulation of commodities.

- It provides a standard measure of value; a means of accounting for value; and it is the measuring unit of prices.

- It is a universally accepted means of payment for goods & services rendered, and for debt obligations.

- It is a means to store value owned, accumulate value, or form hoards of wealth.

-

-

-

-

Fiat money

Once the money-commodity (e.g. gold, silver, bronze) is securely established as a stable medium of exchange, symbolic money-tokens (e.g. bank notes and debt claims) which are issued by the state, trading houses or corporations can in principle substitute for the “real thing”, and this also usually happens, because it is cheaper and more efficient. At first, these "paper claims" (legal tender) are by law convertible on demand into quantities of gold, silver etc., and the circulate alongside precious metals. But gradually currencies are brought into use which are not so convertible, i.e. "fiduciary money" or fiat money which relies on social trust that people will honor their transactional obligations, and that this money will be able to claim goods, assets and services. These kinds of money rely not on the value of money-tokens themselves (as in commodity money), but on the ability to enforce financial claims and contracts, principally by means of the power and laws of the state, but also by other institutional methods. Eventually, as Marx anticipated in 1844, precious metals play very little role anymore in the monetary system.[36]

World money

The ultimate universal equivalent according to Marx is "world money", i.e. financial claims which are accepted and usable for trading purposes everywhere, such as bullion.[37] In the world market, the value of commodities is expressed by a universal standard, so that their "independent value-form" appears to traders as "universal money".[38] Nowadays the US dollar,[39] the Euro, and the Japanese Yen, the currencies of the world's richest and most powerful economies, are widely used as "world currencies" providing a near-universal standard and measure of value. They are used as a means of exchange worldwide, and consequently most governments have significant reserves or claims to these currencies. Nowadays the International Monetary Fund also operates a special fund of world reserve currency, which can be used internationally to augment liquidity, but this isn't used on any very large scale.

In summary

It is important to note that Marx's four steps in the development of the value-form are mainly an analytical or logical progression, which may not always conform to the actual historical processes by which objects begin to acquire a relatively stable value and are traded as commodities.[40] Three reasons are:

- Various different methods of trade (including counter-trade) may always exist and persist side by side. Thus, simpler and more developed expressions of value may be used in trade at the same time, or combined (for example, in order to fix a rate of exchange, traders may have to reckon how much of commodity B can be acquired, if commodity A is traded).

- Market and non-market methods of allocating resources may combine, in rather unique ways. The act of sale, for example, may not only give the owner of a good possession of it, but also grant or deny access to other goods. The actual distinction between selling and barter may not be so easy to draw, and all kinds of "deals" can be done in which the trade of one thing has consequences for the possession of other things.

- Objects which previously had no socially accepted value at all, may acquire it in a situation where money is already being used, simply by imputing or attaching a money-price to them. In this way, objects can acquire the value-form "all at once" - they are suddenly integrated in an already existing market (The only prerequisite is that somebody owns the trading rights for those objects).

It is just that, typically, what the socially accepted value of a wholly new kind of object will be, requires the practical "test" of a regular trading process, assuming a regular supply by producers and a regular demand for it, which establishes a trading "norm" consistent with production costs. A new object that wasn't traded previously may be traded far above or below its real value, until the supply and demand for it stabilizes, and its exchange-value fluctuates only within relatively narrow margins (in official economics, this process is acknowledged as a form of price discovery).[41]

General implications of the value-form analysis

To summarize, the development of the value-form through the growth of trading processes involves a continuous dual equalization & relativization process:

- the worth of products and assets relative to each other is established with increasingly precise equations, creating a structure of relative values;

- behind that, the comparative labour efforts required to make the products are also valued in an increasingly standardized way at the same time. For almost any particular type of labour, it can then be specified, fairly accurately, how much money it would take, on average, to procure it.

Six main effects

Six main effects of this are:

- the process of market-expansion, involving the circulation of more and more goods, services and money, leads to the development of the value-form, which includes and transforms more and more aspects of human life, until almost everything is structured by the value-form (monetized, i.e. the value of everything is expressible in money-prices).

- that it increasingly seems as though economic value ("what things are worth") is a natural, intrinsic characteristic of products and assets (just like the characteristics which make them useful) rather than a social effect created by labour-cooperation;

- what any particular kind of labour is worth, becomes largely determined by the value of the tradeable product of the labour, and labour becomes organized according to the value it produces.

- The development of markets leads to the capitalization of money, products and services: the trade of money for goods and goods for money leads directly to the use of the trading process purely to "make money" from it (a practice known in classical Greece as "chrematistics"). Money is converted into capital, when it is used primarily to make more money, or when it is treated as an asset which can yield a profit or return (a net income). Marx describes this as the inversion of the formula C-M-C' (= a commodity is exchanged for money to buy a different commodity) to M-C-M' (= money is invested in a commodity which, upon sale, obtains more money; that commodity could of course be a different currency).

- Labour power that creates no commodity value or does not have the potential to do so, has no value for commercial purposes, and is therefore usually not highly valued economically, except insofar as it reduces costs that would otherwise be incurred.

- The diffusion of value relations eradicates traditional social relations and corrodes all social relations not compatible with commerce; the valuation which becomes of prime importance is what something will trade for. The end result is the emergence of the circuit M-C...P...C'-M' which indicates that production has become a means for the process of making money (Money buys commodities which are transformed through production into new commodities, and, upon sale, result in more money than existed at the start).

Generalized commodity production

Capital existed in the form of trading capital already thousands of years before capitalist factories emerged in the towns; its owners (whether rentiers, merchants or state functionaries) often functioned as intermediaries between commodity producers. They facilitated exchange, for a price. Marx defines the capitalist mode of production as “generalized commodity production”, meaning that most goods and services are produced primarily for commercial purposes, for profitable market sale. This has the consequence, that both the input and the output of production become tradeable objects with prices, and that the whole of production is reorganized according to commercial principles. Whereas originally commercial trade occurred episodically at the boundaries of different communities, Marx argues,[42] eventually commerce engulfs and reshapes the whole production process of those communities.

In turn, this means what whether or not a product will be produced, and how it will be produced, depends not simply on whether it is physically possible to produce it or on whether people need it, but on its financial cost of production, whether a sufficient amount can be sold, and whether its production yields sufficient profit income. That is why Marx regarded the individual commodity, which simultaneously represents value and use-value as the "cell" (or the "cell-form") in the "body" of capitalism. The seller primarily wants money for his product and is not really concerned with its consumption or use (other than from the point of view of making sales); the buyer wants to use or consume the product, and money is the means to acquire it. Thus the seller does not aim directly to satisfy the need of the buyer, nor does the buyer aim to enrich the seller. Rather, the buyer and the seller are the means for each other to acquire money or goods. As a corollary, production becomes less and less a creative activity to satisfy human needs, but simply a means to make money or acquire access to goods and services.

Reification

The concept of the value-form as an aspect of the commodity form is intended to show how, with the development of commodity trade, anything which has a utility for people (a use-value) can be transformed into a quantity of abstract value, objectively expressible as a sum of money; but, also, how this transformation changes the organization of labour to maximize its value-creating capacity, how it changes social interactions and the very way in which people are aware of their interactions.

However, the quantification of objects and the manipulation of quantities ineluctably leads to distortions (reifications) of their qualitative properties. Albert Einstein is supposed to have remarked[43] that "Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted." For the sake of obtaining a measure of magnitude, it is frequently assumed that objects are quantifiable, but in the process of quantification, various qualitative aspects are conveniently ignored or abstracted away from. Obviously the expression of everything in money prices is not the only valuation that can, or should, be made.

Essentially, Marx argues that if the values of things are to express social relations, then, in trading activity, people necessarily have to "act" symbolically in a way which inverts the relations among objects and subjects, whether they are aware of that or not. They have to treat a relationship as if it is a thing in its own right. In an advertisement, a financial institution might for example say "with us, your money works for you", but money does not "work", people do. A relationship gets treated as a thing, and a relationship between people is expressed as a relationship between things.

In Postmodernist culture, this inversion is acknowledged, but an explicit attempt is made to recognize the social relationship involved and its meaning for Self and Other; the idea is that, in so doing, an otherwise impersonal, estranged or superficial trading contact can be "humanized". The question remains how one can know that this attempt is authentic and what its real motivation is.

Commodification

The total implications of the development of the value-form are much more farreaching than can be described in this article, since (1) the processes by which the things people use are transformed into objects of trade (often called commodification, commercialization or marketization) and (2) the social effects of these processes, are both extremely diverse. A very large literature exists about the growth of business relationships in all sorts of areas. For capitalism to exist, markets must grow, but market growth requires changes in the way people relate socially, and changes in property rights. This is often a problem-fraught and conflict-ridden process, as Marx describes in his story about primitive accumulation.

Value-form and price-form

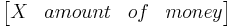

In his story, Marx defines "value" simply as the ratio of a physical quantity of product to a quantity of average labour-time, which is equal to a quantity of gold-money (in other words, a scalar):

-

-

-

-

- X quantity of product = Y quantity of average labour hours = Z quantity of gold-money

-

-

-

He admits early on, that the assumption of gold-money is a theoretical simplification,[44] since the buying power of money units can vary due to causes which have nothing to do with the production system (within certain limits, X, Y and Z can vary independently of each other); but he thought it was useful to reveal the structure of economic relationships involved in the capitalist mode of production, as a prologue to analyzing the motion of the system as a whole; and, he believed that variations in the buying power of money did not alter that structure at all, insofar as the working population was forced to produce in order to survive, and in so doing entered into societal relations of production independent of their will; the basic system of property rights remained the same.

As any banker or speculator knows, however, the expression of the value of something as a quantity of money-units is by no means the “final and ultimate expression of value”.[45]

- At the simplest level, the reason is that different “monies” (currencies) may be used side by side in the trading process, meaning that “what something is worth” may require expressing one currency in another currency and that one currency is traded against another, where currency exchange rates fluctuate all the time. Thus, money itself can take many different forms.

- In more sophisticated trade, moreover, what is traded is not money itself, but rather claims to money (“financial claims”, for example debt obligations or stocks which provide the holder with a certain income).

- And in even more sophisticated trade, what is traded is the insurance of financial claims against the risk of possible monetary loss. In turn, money can be made just from the knowledge about the probability that a financial trend or risk will occur or not occur. Eventually financial trade becomes so complex, that what a financial asset is worth is often no longer expressible in any exact quantity of money (a “cash value”) without all sorts of qualifications, and that its worth becomes entirely conditional on its earnings potential, i.e. how much extra money could be obtained from owning title to the asset, or from selling it at a future date.

In Capital Volume 3, which he drafted before Volume I, Marx shows he was well aware of this. He distinguished not only between "real capital" (physical, tangible capital assets) and "money capital", but also noted the existences of "fictitious capital" and "pseudo-commodities" which have exclusively symbolic value (which, however, can be converted into real product value through trade). Marx believed that a failure to theorize the value-form correctly led to "the strangest and most contradictory ideas about money" which "emerges sharply... in [the theory of] banking, where the commonplace definitions of money no longer hold water".[46]

The price-form

Consistent with this, Marx explicitly introduced a distinction between the value-form and the price-form early on in Capital, Volume I. Simply put, the price-form is a mediator of trade which is separate and distinct from the value-form.

What are prices?

If we want to trade goods for money, or money for goods, or if we want to trade a financial asset, we need to know how much we have to pay or what something will sell for. Prices tell us how much in money-quantities; they express exchange-value in money terms. Prices are not money themselves, but they indicate money-quantities. They symbolize how much money is required in exchange, to trade and acquire something.[47] Thus, prices are ways to express and inform about how much money is involved in any kind of (potential) transaction, or what it takes (financially speaking) to make the transaction (of course, price information can itself also be sold for money, and people might deliberately buy or sell things, with the aim to push up or lower a particular price-level).

Essentially, therefore, a price is a "sign" which conveys information about either a possible or a realized transaction (or both at the same time). The information may be true or false; it may refer to observables or unobservables; it may be estimated, assumed or probable. However, because prices are also numbers, it is easy to treat them as manipulable "things" in their own right, in abstraction from their appropriate context. This can inspire all kinds of price calculations which are rather dodgy, because they express a valuation or interpretation which, in reality, is conditional on many assumptions, including the reality of many other prices.

The price resulting from a calculation may be regarded as symbolizing (representing) one transaction, or many transactions at once, but the validity of this "price abstraction" all depends on whether the computational procedure is accepted. The use of price idealizations for the purpose of accounting, estimation and theorizing has become so habitual and ingrained in modern society, that they are frequently confused with the real prices actually realized in trade.

Price and value concepts

According to Marx, the price-form is not a “further development” of the value-form, for three reasons:

- As Marx notes, prices may be attached to almost anything at all ("the price of owning, using or borrowing something"), and therefore need not express product-values at all. They may only express that "somebody owes somebody else some money". Prices do not necessarily have anything to do with the production of tangible wealth, although they might facilitate claims to it.

- Insofar as the price of a commodity does express its value accurately, this does not necessarily mean that it will actually trade at this price; products can trade at prices above or below what the goods are really worth, or fail to be traded at any price.

- Although as a rule there will be a strong positive correlation between product-prices and product-values, they may change completely independently of each other for all kinds of reasons. When things are bought or sold, they may be over-valued or under-valued due to all kinds of circumstances.

Value relationships among physical products and assets - as proportions of current labour effort involved in making them - exist according to Marx quite independently from price information, and prices can oscillate in all sorts of ways around economic values, or indeed quite independently of them. That is why Marx felt quite comfortable about mostly ignoring price fluctuations in the first stages of his value theory. In his pamphlet Wages, Price and Profit, he notes:

"Supply and demand regulate nothing but the temporary fluctuations of market prices. They will explain to you why the market price of a commodity rises above or sinks below its value, but they can never account for that value itself. Suppose supply and demand to equilibrate, or, as the economists call it, to cover each other. Why, the very moment these opposite forces become equal they paralyze each other, and cease to work in the one or the other direction. At the moment when supply and demand equilibrate each other, and therefore cease to act, the market price of a commodity coincides with its real value, with the standard price round which its market prices oscillate. In inquiring into the nature of that value, we have, therefore, nothing at all to do with the temporary effects on market prices of supply and demand."[48]

Mutual influence of values and prices

If prices for products rise, hours worked may rise, and if prices fall, hours worked may fall (sometimes the reverse may also occur, to the extent that extra hours are worked, to compensate for lower income resulting from lower prices, or if more sales occur because prices are lowered). In that sense, it is certainly true that prices and values mutually influence each other. It is just that, according to Marx, product-values are not determined by the labor-efforts of any particular enterprise, but by the combined result of all of them. That social valuation exists as a given social fact, quite independently of any price fluctuations. For example, the price of a particular brand of a new car might vary between $15,000 and $20,000, but it will normally never sell for "$2" or "$200,000", regardless of consumer appetites. Quite simply, the new car is considered to be worth around $17,500 on average, and that valuation (a standard supply price) normally does not change much, no matter what people do. The car will neither be supplied at a cost of $2 nor at a cost of $200,000.

Real prices and ideal prices

In discussing the form of prices in the Grundrisse and Das Kapital, Marx drew an essential distinction between actual prices charged and paid, i.e. prices which express how much money really changed hands, and various “ideal prices" (imaginary or notional prices).

Complexity of prices

Because prices are symbols or indicators in more or less the same way as traffic lights are, they can symbolize something that really exists (e.g. hard cash) but they can also symbolize something which doesn’t exist, or symbolize other symbols. That can make the forms of prices highly variegated, flexible and complex to understand, but also potentially very deceptive, disguising the real relationships involved. Consequently, as Marx notes in the Grundrisse, the knowledge of prices itself became a specialized science.[49]

Modern economics is largely a "price science" (a science of "price behaviour"), in which economists attempt to analyze, explain and predict the relationships between different kinds of prices - using the laws of supply and demand as a guiding principle. This however was not Marx's primary concern; he focused rather on the structure and dynamics of the capitalist system as a whole. His concern was with the overall results to which market activity would lead.

Vulgar economics

In what Marx called “vulgar economics”, the complexity of the concept of prices is ignored however, because, Marx claimed, the vulgar economists assumed that:

-

-

-

- all prices belong to the same object class (they are qualitatively the same, and differ only quantitatively, irrespective of the type of transaction with which they are associated, or the valuation principles used).

- “price” is just another word for “value”, i.e. value and price are identical expressions.

- prices are always exact, in the same way that numbers are exact.

- price information is always objective (it is never influenced by how people regard that information).

- people always have equal access to information about prices, in which case swindles are merely an aberration from the normal functioning of markets (rather than an integral feature of them, which requires continual policing).

- the price for any particular type of good is always determined everywhere in exactly the same way, according to the same economic laws, regardless of the given social set-up.

-

-

In his critique of political economy, Marx denied that any of these assumptions were scientifically true. He distinguished carefully between the values, exchange values, market values, market prices and prices of production of commodities. However he did not analyze all the different forms that prices can take (for example, market-driven prices, administered prices, accounting prices, negotiated and fixed prices, estimated prices, nominal prices, or inflation-adjusted prices) focusing mainly on the value proportions he thought to be central to the functioning of the capitalist mode of production as a social system.

The effect of this omission was that debates about the relevance of Marx's value theory became confused, and that Marxists repeated the same ideas which Marx himself had rejected as "vulgar economics". In other words, they accepted a vulgar concept of price.[50] Prices can exist in all kinds of different economic systems which operate some kind of currency or credit system, but that does not mean that prices always function in the same way. In different economic systems and during different economic periods in history, price-accounting systems have had quite different effects. It is certainly possible to draw an analogy between prices in one sort of economic system and prices in another economic system, but the analogy well may be false. It cannot be assumed that all price-accounting systems always work in the same way, because the specific social processes and social relations involved may create quite different relationships of cause and effect.

The world of price abstractions

The main analytical point here is that, precisely because of the tricky characteristics of the price-form which Marx already mentions, the world of prices can be a very false world, which disguises the real economic relationships, instead of making them transparent. Fluctuating price signals serve to adjust product-values and labour efforts to each other, in an approximate way; prices are mediators in this sense. But that which mediates should not be confused with what is mediated. Thus, if the observable price-relationships are simply taken at face value, they might at best create a distorted picture, and at worst a totally false picture of the economic activity to which they refer.

At the surface, prices might quantitatively express an economic relationship in the simplest way, but in the process they might abstract away from other features of the economic relationship which are also very essential to know. Indeed, that is another important reason why Marx's analysis of economic value largely disregards the intricacies of price fluctuations; it seeks to discover the real economic movement behind the price fluctuations.

Quote by Marx on the relationship between the value-form and the price-form

"Every trader knows, that he is far from having turned his goods into money, when he has expressed their value in a price or in imaginary money, and that it does not require the least bit of real gold, to estimate in that metal millions of pounds’ worth of goods. When, therefore, money serves as a measure of value, it is employed only as imaginary or ideal money. This circumstance has given rise to the wildest theories. But, although the money that performs the functions of a measure of value is only ideal money, price depends entirely upon the actual substance that is money. (...) The possibility... of quantitative incongruity between price and magnitude of value, or the deviation of the former from the latter, is inherent in the price-form itself. This is no defect, but, on the contrary, admirably adapts the price-form to a mode of production whose inherent laws impose themselves only as the mean of apparently lawless irregularities that compensate one another. The price-form, however, is not only compatible with the possibility of a quantitative incongruity between magnitude of value and price, i.e., between the former and its expression in money, but it may also conceal a qualitative inconsistency, so much so, that, although money is nothing but the value-form of commodities, price ceases altogether to express value."[51]

Engels on the value-form

Friedrich Engels comments on the value-form concept in Part 3 chapter 4 of his 1876-1878 book Anti-Dühring which was written with Marx's approval, emphasizing how the growth of commodity trade breaks up the social fabric of traditional societies:

"Commodity production... is by no means the only form of social production. In the ancient Indian communities and in the family communities of the southern Slavs, products are not transformed into commodities. The members of the community are directly associated for production; the work is distributed according to tradition and requirements, and likewise the products to the extent that they are destined for consumption. Direct social production and direct distribution preclude all exchange of commodities, therefore also the transformation of the products into commodities (at any rate within the community) and consequently also their transformation into values. (...) The concept of value is the most general and therefore the most comprehensive expression of the economic conditions of commodity production. Consequently, this concept contains the germ, not only of money, but also of all the more developed forms of the production and exchange of commodities. (...) The value form of products... already contains in embryo the whole capitalist form of production, the antagonism between capitalists and wage-workers, the industrial reserve army, crises. (...) Once the commodity-producing society has further developed the value form, which is inherent in commodities as such, to the money form, various germs still hidden in value break through to the light of day. The first and most essential effect is the generalisation of the commodity form. Money forces the commodity form even on the objects which have hitherto been produced directly for self-consumption; it drags them into exchange. Thereby the commodity form and money penetrate the internal husbandry of the communities directly associated for production; they break one tie of communion after another, and dissolve the community into a mass of private producers.[52]

Scientific criticism

There are five main lines of scholarly criticism of Marx's idea of the value-form:

Obscurantism

The criticism most often heard from the critics of Marx, such as Karl Popper, Friedrich von Hayek, Ian Steedman and Francis Wheen is that, even if Marx himself meant well, Marx’s value-form idea is simply an esoteric obscurantism, “dialectical hocus pocus” or “mumbo jumbo”.[53] The Marxist Rosa Luxemburg likewise complained about the “horror” of Marx’s unnecessary “Hegelian rococo” in Das Kapital.[54]

Spurious rigour

Marx's argument does not really make coherent scientific sense, it is argued – quite possibly because Marx tried to do too much at once. That is, at one and the same time, one finds Marx

- trying to respond to the classical discourses of the political economists about “the commodity”, “exchange-value”, “use-value” etc. in an erudite way;

- also poking fun at, and setting traps for what he regarded as pedantic, pseudo-profound German professors prattling about “dialectics”;

- at the same time as trying to tell an entertaining story using literary and theatrical metaphors that would really sell (unlike his previous book, the super-abstract and boring A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy);

- and trying to make a substantive, serious argument about the historical origin and essential nature of economic value.

The result, some critics feel, is a series of devastating ambivalences and ambiguities, which cover up all kinds of illogical moves - moves which, they claim, are fatal to Marx’s argument. This is a criticism along the lines that one ought not to take Marx’s story seriously, as a scientific argument about economics (modern economists will nowadays often agree that the theory of economic value raises difficult problems, but they consider that such supremely abstract theoretical difficulties have no real bearing on practical economics).

Gerald Cohen

Often, Marxists have replied to this type of criticism by restating Marx’s arguments in clearer language, or by showing that Marx’s theory of economic value at the very least fares no worse than the subjective theory of value (the theory of the util as the measuring unit of utility). Even so, when he published his very clear restatement Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence,[55]the Marxist philosopher Gerald Cohen explicitly dissociated himself from Marx’s value theory. Cohen argued that it is possible to have an historical materialism without a labour theory of value, because the one does not logically entail the other as well. This interpretation contrasts with Lenin's opinion - repeated by Johann Witt-Hansen[56] - that with the appearance of Das Kapital, "the materialist conception of history is no longer a hypothesis, but a scientifically proven proposition".[57]

The substance of value

Whereas many economists and philosophers have been inspired by Marx's analysis of the value-form, they have usually rejected the thrust of Marx's argument, namely that the substance of product-value is the expenditure of human labor effort in general, i.e. abstract labour.

Commensurability

Marx insists that:

"It is not money that renders the commodities commensurable. Quite the contrary. Because all commodities, as values, are objectified human labour, and therefore in themselves commensurable, their values can be communally measured in one and the same specific commodity, and this commodity can be converted into the common measure of their values, that is into money. Money as a measure of value is the necessary form of appearance of the measure of value which is immanent in commodities, namely labour-time."[58]

Marx's argument is that the exchangeability of commodities according to their value is based on the common factor that all of them are products of social labour (co-operative human labour producing things for others).

- Ordinary working people know very well that their work effort is valuable and represents a value. That's because they do the work; it has real consequences for their lives. But what exactly that value is, objectively speaking, is often much more difficult to establish - it becomes apparent only in the comparison of products when they are exchanged.

- If free citizens cannot produce everything they need themselves, they have to trade to get what they want, money or no money, but in doing so they also have to acknowledge the valuation of other free citizens' labor efforts in terms comparable or equal to their own (things might be different if goods and services are provided by slaves, such as in the Greek society that Aristotle lived in).[59] Thus, the exchange process mediating the activities of producers and consumers represents effectively the value abstraction of human labour by means of shared symbols and symbolic objects.

- In principle, economic value does not exist because money exists to express economic value; money exists because economic value exists. Consequently, Marx argues, we have to be able to explain economic value and its origin quite independently of the existence of money. The analysis of the value-form is intended precisely as a demonstration of this idea, by showing how the money-relationship actually and necessarily originates out of the exchange of wares in an increasingly complex division of labour (irrespective of the precise details of how this process historically occurs).

Price alternative

Critics however argue that Marx's argument is simply not logically compelling.

- They claim that we could just as well argue that what makes products exchangeable is simply the "common factor" that they have a price, or that a price can in principle be attributed to them; or even more simply, that people just have a common desire to exchange products for money. If that common desire exists, it is argued, nothing else is necessarily required in order to exchange products.

- Although the very word "price" (in the sense of a money-price) was unknown prior to the 13th century AD,[60] it is argued that prices have nevertheless always existed in some form in human society. The same thing that Marx tries to explain using the notion of "value" could, it is argued, just as well be explained in terms of the supply and demand for priced goods among individuals and groups who interact with each other.

- Thus, while Marx's observations might be of sociological or anthropological interest, it is argued they fail to provide any logically decisive proof that human labour is the substance of economic value. Approximately at the same time as Marx published his theory in 1867, Stanley Jevons for instance proposed that price fluctuations could be explained in terms of utility and the subjective preferences of buyers and sellers.[61] This recalls Aristotle's idea (mentioned above) that goods have value because people want them.

Unoist approach

For this reason, the Japanese Marxist scholar Kozo Uno argued in his classic Principles of Political Economy that Marx's original argument had to be revised.[62] In the revised version, the theory of the value-form is integrated in the theory of commodity circulation, and does not refer to the substance (content) of value at all. The substance of value as labour then becomes apparent and is theoretically demonstrated only in the analysis of the production of commodities "by means of commodities".

Some Western Marxists do not find this Unoist approach very satisfactory however, because of Marx's basic insistence that the formation of product values is an outcome of both the "economy of labour-time" and "the economy of trade", i.e. commodity values are originally formed through mutual adjustments of the processes of producing commodities and circulating (trading) commodities. Since exchanging products itself takes work, however - "circulation costs" - human labour and trade are in reality inseparable at any time. A product cannot be traded, unless it is produced, regardless of how specifically it is produced.

The results of accumulation

An additional complication is that, as the accumulation of capital grows, more and more durable assets exist external to the sphere of production. Marx was primarily concerned with the value of newly produced commodities, but it is unclear from his theory about the capitalist mode of production what determines the value of the growing stock of durable assets which is neither an input nor an output of current production.

In developed capitalist countries, nowadays only around a quarter or or a fifth of the stock of physical capital assets consists of privately owned means of production.[63] The rest of the physical assets consists of all kinds of real estate (e.g. non-productive land and parks, buildings and structures), infrastructural works & installations (e.g. transport and communication systems, water & land management systems) and consumer durables (personal belongings, furnishings, vehicles, equipment etc.). To the physical capital assets must be added a large stock of financial assets (mainly savings and deposits, stocks, and all kinds of securities).

So, in developed capitalist societies, the capital directly tied up in means of production is perhaps only about one-sixth or one-seventh of the total social capital. As a result, the vast majority of workers in developed capitalist societies are no longer directly employed anymore to produce new products in farming, forestry, fishing & hunting, mining, construction or manufacturing; instead, they are mainly employed in maintaining, distributing and managing already existing products, property and assets. It is certainly true, that many of such "service industries" really also produce products, or are a technically indispensable indirect input to producing products (services previously supplied inside the factory are outsourced to other locations, and therefore are no longer classified as "manufacturing"). Nevertheless, in the modern division of labour of developed capitalist countries, the workers in private enterprise involved directly in producing new tangible goods for sale are in the minority. Ultimately, that fact reflects the enormous increase in the physical productivity of mechanized production.

This issue was seriously studied by Michael Hudson (economist). Particularly since the economic slump of 2008/2009, there are more and more attempts to develop new social accounts providing detailed estimates for household wealth and household transactions. The economic reason for that is, that if assets owned by households suddenly lose a lot of value, for example because a bubble economy pops, this drop in value can have very large consequences for household incomes and buying power - which, in turn, has a very large effect on the economy as a whole.

The usefulness of value theory

This criticism is basically that all the problems which Marx tries to solve with his theory of the forms of value can be solved much better and more plausibly with modern price theory.

Meek and Steedman

In a 1975 paper subtitled "Was Marx's Journey Really Necessary?", the influential Marxist economist Ronald L. Meek argued that Marx's value theory had become redundant. Its problems could be resolved using the insights of Piero Sraffa, so that the old value theory was unnecessary:

"With the specification where necessary of the appropriate institutional datum, and with remarkably little modification and elaboration, a sequence of Sraffian models can be made to do essentially the same job which Marx's labour theory of value was employed to do. We can start, as Marx did, with the postulation of a prior concrete magnitude which limits the levels of profit and rent. We can adopt the same kind of view about the order and direction of determination of the variables in the system as Marx did. Up to a point, the same kind of quantitative predictions about the relation between price ratios and embodied labour ratios can (if we wish) be made; and the analysis based on the models can readily be framed (again if we wish) in logical-historical terms. The same kind of scope can be left for the influence of social and institutional factors in the distribution of income; and the transformation problem (or its analogue) can be solved in passing, as it were, without any fuss whatever. In the light of all this, the fact that we do not need to tell our Sraffian equations anything at all about Marxian values seems superbly irrelevant."[64]

The argument (similar arguments are presented by Ian Steedman)[65] is that value theory is unnecessary, because all economic relationships can be described and explained in terms of prices. The Marxist response to this criticism[66] was extremely weak; most Marxists had accepted the conventional price-theories of economics as largely correct and unproblematic,[67] and just kept insisting that value-theory was a necessary "add-on" to make sense of the economy.[68]

Value-form School

From the 1970s, the so-called "value-form theorists" ("value-form school") have emphasized - influenced by Theodor W. Adorno and the rediscovery of the writings of Isaak Illich Rubin[69] - the importance of Marx's value theory as a qualitative critique - a cultural, sociological or philosophical critique of the reifications involved in capitalist commercialism. The value-form school has become very popular especially among Western Marxists who are not economists.

Examples in the English language literature are Christopher J. Arthur [46], Tony Smith [47], Alfred Sohn-Rethel,[70] Moishe Postone[71] and Geert Reuten & Michael Williams.[72] Noted German-language value-form theorists are the Marx-scholars Hans-Georg Backhaus,[73] Helmut Reichelt[74] Michael Heinrich[75] (Neue Marx-Lektüre[76]) and Nadja Rakowitz[77] (de:Wertkritik), as well as the Sydney-Constance Project (Michael Eldred,[78] Marnie Hanlon, Lucia Kleiber, Mike Roth).

Supporters of the "value-form school", especially in Germany and Britain, think that it is deeply meaningful, profound and super-radical - especially because it depicts Marx's theory as completely different and disconnected from any other economic theory. On the other hand, the critics of the value-form school see this tradition simply as an "evasive tactic", staged by Marxist scholastics who are usually not well-trained in economic science, and who are therefore not able to rebut effectively the attacks made against Marx by economists.

Autonomism and Negri

Value-form theory has also been popular among intellectual supporters of Autonomism[79] and Anarchism,[80] although Antonio Negri thinks the theory is outdated now:

"The definition of the form of value which we find in Karl Marx's Capital is completely internal to what we have called the first phase of the second industrial revolution (the period 1848-1914). But the theory of value, formulated by Ricardo and developed by Marx, is in effect formed in the previous period, the period of "manufacture," during the first industrial revolution. This is the source of the theory's great shortcomings, its ambiguities, its phenomenological holes, and the limited plasticity of its concepts. Actually, the historical limits of this theory are also the limits of its validity, notwithstanding Marx's efforts, at times extreme, to give the theory of value the vigor of a tendency."[81]